When it comes to storytelling, it’s hard to go wrong with a plot involving a “cursed” film production.

Other than the fact that some people believe this is a real thing (see Poltergeist), it’s just inherently entertaining. We savor the idea of someone’s spirit’s having been disturbed or angered by the perceived audacity of a filmmaker who wants to explore a story that is apparently better left alone. Superstitions like this one fascinate us because they ostensibly indicate the influence of mysterious forces that somehow manipulate the world as we know it and imbue it with a species of logic that we can never possibly understand. They let us peek behind the curtain, but we only see shadowed figures moving about, and their movements are inscrutable.

This idea predates the invention of film. After all, who can forget the taboo of saying Macbeth in a theater? It’s just that movies are now an indispensable aspect of our culture and are, as such, always in the public consciousness. I have no idea where this idea first showed up, but the first time I encountered it was, like so many things, in an episode of Scooby-Doo. It’s been ages since I’ve seen it, and all I can remember about it is that a monstrous gorilla was trying to wreck a movie. I don’t recall what was supposed to have pissed the gorilla off, but, as with all Scooby-Doo episodes, it turned out that there was an ulterior motive and that the gorilla was just used to distract people from what was really going on. It was disappointing, if predictable, when the gorilla was unmasked as the stuntman or something, but it was undeniably interesting before the “reveal.”

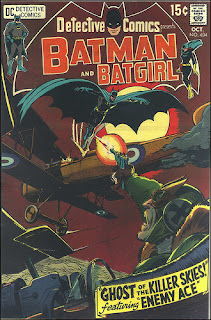

In Detective Comics #404, “Ghost of the Killer Skies,” Bruce Wayne is in Spain overseeing the production of a film that he is helping finance. (We accept this premise because Bruce has an insane amount of money and probably gets bored from time to time.) It becomes clear right off the bat (no pun intended) that things are not going as planned when a plane being used in the movie crashes into the side of a mountain and bursts into flames. Batman (for reasons that are not entirely clear) witnesses the crash and pulls the pilot out of the fiery wreckage, only to find that he has been strangled.

The director, Anson (I assume this is his surname, as it is the only name he is ever given), and the cameraman, Gavin, quickly arrive on the scene, and, regarding the burning plane and dead pilot, the former remarks that there has been “nothing but trouble since [they] started.”

“Props,” he continues, “are missing…film-stock catches fire…sound tracks get accidentally erased…and now this.” (You know: the kinds of things that directors get upset about.) Having changed back into his civilian identity, Bruce proposes that a meeting be called to assess the situation and see what steps can be taken to get things back on track.

The film, tentatively titled The Hammer of Hell, concerns German pilot Baron Hans von Hammer (known to Silver-Age DC fans as Enemy Ace). Over budget and facing competition from similar productions, Anson considers abandoning the film, but Bruce maintains that it’s a unique story that needs to be told.

During the meeting, Heinrich Franz, the film’s “technical expert,” shows up, suggesting that the film should be shelved, as he believes von Hammer’s ghost is plaguing its production. Bruce goes back to his hotel to do some research and finds that Franz is a dead ringer for von Hammer. Donning his costume, he heads to the set under the cloak of darkness to investigate and finds a group of men trying to destroy the planes with dynamite.

After dispatching the perpetrators, Batman realizes that Gavin is behind the sabotage attempt and confronts him in his trailer, revealing that he knows a rival film company paid him off. Suddenly, shots ring out, and Anson collapses in the doorway, claiming that the ghost of von Hammer fired on him. Gavin absconds, but Batman subdues him just in time to hear the roar of plane engines. Turning around, the Dark Knight finds the “ghost” holding him at gunpoint.

It comes as no surprise that the mastermind behind the attacks is Franz. A descendant of von Hammer, he believes that the film is an insult to the memory of his ancestor. Rather than shoot Batman outright, Franz agrees to engage in an aerial dogfight with him. It becomes clear in short order that Franz is the superior pilot (coupled with the fact that he has a Luger), but Batman relies on his instincts and quick thinking. Leaping from his plane, the Caped Crusader latches on to the wing of Franz’s craft and attempts to wrench the gun from his foe’s grasp. The struggle concludes when Franz’s scarf gets snagged in the propeller, and he falls to his death.

Batman lands and ruminates on how the love of war, with which Franz was clearly inflicted, is a destructive thing indeed.

Written by Denny O’Neil and illustrated by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano, “Ghost of the Killer Skies” is really a love letter to the Enemy Ace stories of Joe Kubert and Robert Kanigher and is frequently considered a classic in Batman’s canon. Adams’ dynamic storytelling and photorealistic renderings give the story a cinematic feel (appropriately enough) that synthesizes the essence of its source material and pushes it to levels never believed possible. Bear in mind that while Adams’ art still impresses us today, when it was new it was nothing short of revolutionary. The amount of detail he packs into each panel is staggering, and the characters seem so real that they virtually leap off the page. No other artist could have done this story justice.